- The federal Highway Transportation Fund has been short for years and now federal politicians want to raise the gasoline tax for the first time in nearly 20 years, but some experts believe that’s exactly the opposite of what should be done

Lawmakers – including, unfortunately, some Republicans – have issued a call recently to raise the federal gasoline tax as a way to address impending shortfalls of billions of dollars in the federal highway and transportation fund. It’s bad enough hearing any politician cite the need for yet another federal tax that would be borne mostly by the poor and middle class, but it is especially frustrating to hear politicians who hail, ostensibly, from the party of smaller, less intrusive government claim that a government already spending $4 trillion a year needs more of our money.

Still, there is a real need to bolster highway funding. As noted by Veronique de Rugy, senior research fellow at the Mercatus Center at George Mason University in a recent post, Congress has had to transfer some $60 billion from general funds to the highway fund since 2008 because of shortfalls.

Nevertheless, she doesn’t think raising the federal gas tax to generate more revenue is the right approach, despite the fact that there is a drop in gasoline prices that is liable to be temporary.

She favors abolishing the tax altogether.

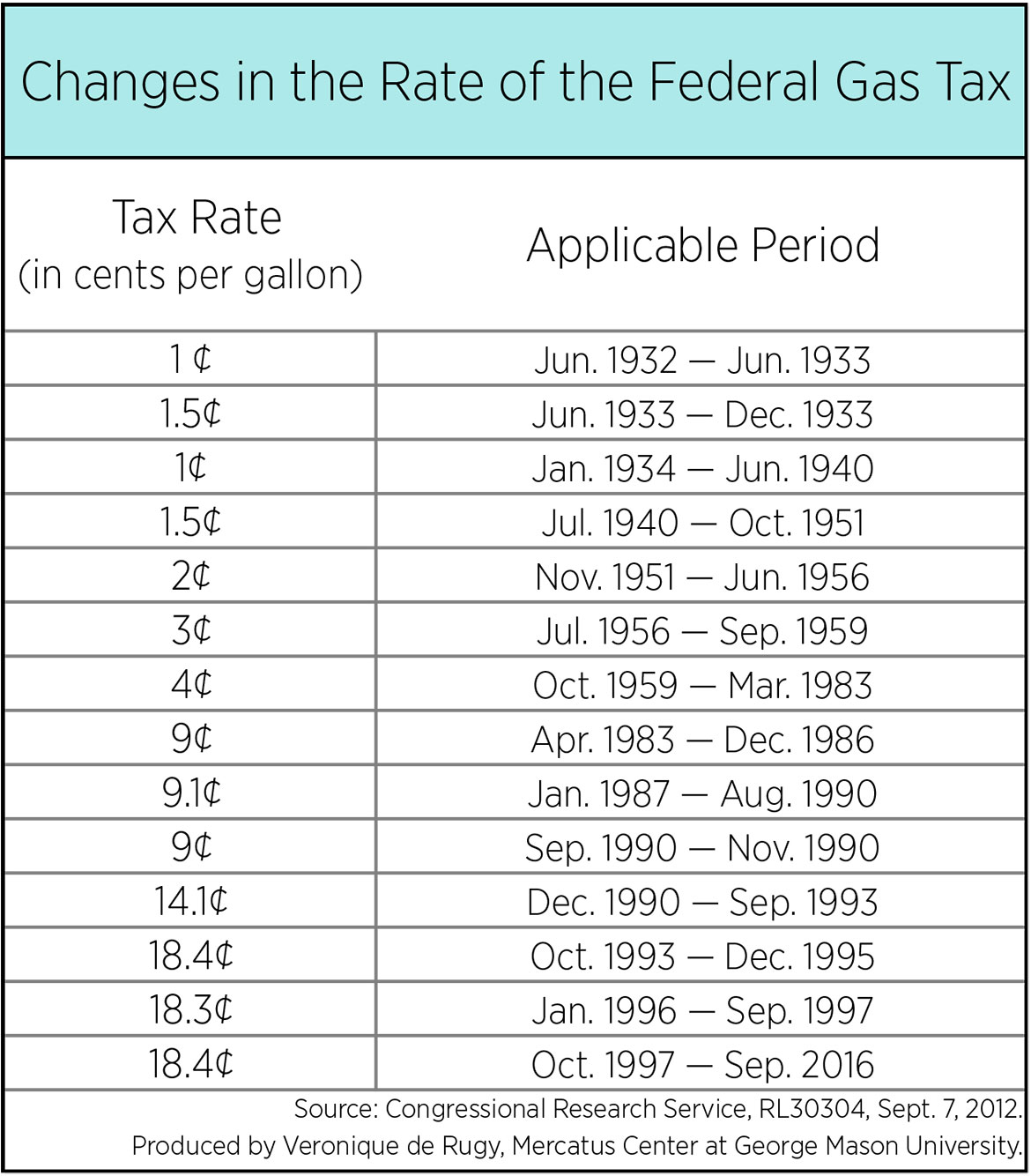

Originally created as a temporary deficit-reduction measure in 1932, the federal gas tax has turned into a permanent levy that has enabled the federal government to play an oversized role in infrastructure policy—a role that had traditionally been left to state and local governments and the private sector,” she writes. “It is time to return that responsibility to where it belongs and get rid of the federal gasoline tax,” which is currently 18.4 cents per gallon and has not been raised since the mid-1990s.

De Rugy notes that until the 1950s, the federal gas tax was a mechanism used to fund some of the federal government’s regular obligations. But when the development of the national interstate system beginning around 1956, revenues from the tax were to be considered as a sort of “user fee,” and were to be dedicated to a newly created Highway Trust Fund.

As is usually the case with government programs, however, the HTF was expanded in the out years to cover transit projects and other pet initiatives that did not serve as a benefit to the nation as a whole. And as those projects expanded, so, too, did the gasoline tax. The tax effectively doubled after two sizeable increases in the early 1990s; they were used, in part, for budget deficit reduction.

By the end of the century, the doubled rate increase nevertheless remained intact, but at least by then gas taxes were once again dedicated solely to the HFT. “History had essentially repeated itself,” de Rugy wrote, adding:

Policymakers quick to point out that the current 18.4 cent per gallon rate hasn’t increased since the mid-1990s and, correctly, that price inflation has effectively eroded the “purchasing power” of the gas tax. The tax has also generated less revenue as motor vehicles have become more fuel efficient. Proponents of federal infrastructure spending act as if there are no alternatives to the ongoing budget shortfalls in the HTF than to raise the rate, find additional sources of revenue, or both. Opponents of raising the gas tax have been content to argue that the federal government should simply spend an amount equal to the revenue received. While that would certainly be preferable to a tax increase, abolishing the tax would be better still.

De Rugy asks, then, what sense does it make to collect taxes from the states, filter them through the maze (and expense) of Washington’s federal bureaucracy, only to send it back to the states? And yet, that is the nature of the current system.

She recommends axing the federal gas tax in favor of devolving power back to the states:

Instead, state policymakers who believe that their state needs more money for infrastructure projects should make the case to their constituents that taxes should be increased to fund such endeavors. With the federal gas tax out of the way, such proposals would perhaps become an easier sell.

If that is too much for state lawmakers to handle, then she notes that could lead to creative, alternative financing methods instead, such as privatization.

“The beauty of allowing the states to re-assume responsibility for infrastructure policy is that it would encourage innovation and competition,” she says. “The states would also be free of the federal mandates that come with receiving funds from the federal government. For example, federal Davis-Bacon rules require workers on federally funding projects to be paid the typically higher ‘prevailing wage,’ which unnecessarily increases the cost of projects by approximately 10 percent.”

Giving states and taxpayers choices and better deals has never been a consideration in the current federal gas tax and highway-funding scheme. But good ideas – even just different ideas – don’t often get much consideration in the nation’s capital, where politicians from both sides of the aisle tend to eschew devolvement of power to the states. De Rugy notes, however, that leaving the decision-making to Washington’s politicians and highway bureaucrats gets them off the hook for making tough funding decisions.

“Although state policymakers often complain about Washington’s heavy-handedness, they also enjoy the political benefits of spending money on projects that didn’t require their voters to bear the full burden,” she writes.

But, “that makes it all the more important for proponents of limited government to push back against the status quo and resume responsibility for infrastructure—and, in the process, restore a more vigorous vision of federalism,” she said.

Not everyone agrees, however. Tim Worstall, who blogs about economics, finance and public policy over at Forbes, believes linking a taxing mechanism to a particular activity – gasoline taxes to highway construction – makes no sense because the amount of taxes the government collects for a particular activity may not produce the level of revenue needed to spend on a particular budget line item.

Indeed, Worstall believes the gas tax is a “good” one and thus should be raised to $1 a gallon, but with this caveat: Raise the good gasoline tax while eliminating other bad taxes:

[W]e do need to recognise that we’re going to have government. And that means that we’re going to have taxes to pay for it. So, on the assumption that all revenue simply goes into one pot which is then allocated, the gasoline tax is a very good idea indeed. For we know several things about taxation: one of them being that all taxes have deadweight costs. …

Consumption taxation is lower than income taxation in deadweight costs, both are lower than capital and corporate taxation. Excellent: we obviously want to raise our necessary tax revenue at the least cost so therefore a consumption tax, like an excise tax on gasoline, is a “good” tax.

Worstall agrees with de Rugy that the HTF should be abolished, but he also accepts the Left’s position that global warming is actually occurring and therefore backs an addition 60 cents a gallon in taxation – a carbon tax – to provide funding for that line item. His full piece is here.

The level of taxation required to supply Congress with funds to carry out its Article I duty to “post roads” is a matter of debate, but what cannot be argued, in our view, is that Washington’s gas-tax formula is archaic and in need of reform. Simply pouring more money into the existing federal scheme is an idea that ought to be dead on arrival.

Jon E. Dougherty is the editor of Absolute Rights. His bio is here. Follow him on Twitter.

What are YOUR thoughts about the federal gasoline tax and highway funding mechanism? Should lawmakers raise the federal gas tax? If so, by how much? Or should Congress abolish it altogether and let the states get creative in how they want to fund their own highway initiatives? TELL US below!

The post Raise the federal gas tax? How about we repeal it instead appeared first on Absolute Rights.